Hold on tight, because the story I’m about to tell you is about a master of surrealism who decided to play with botany like a child with Legos through his series of Flordali works !

In the late 1960s, Salvador Dalí , that genius prankster, took over the

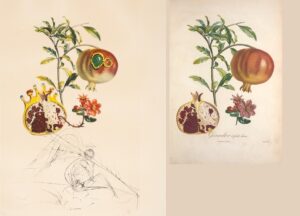

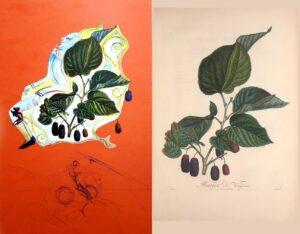

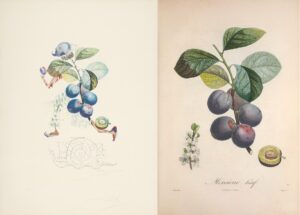

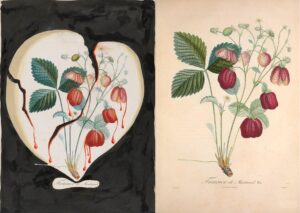

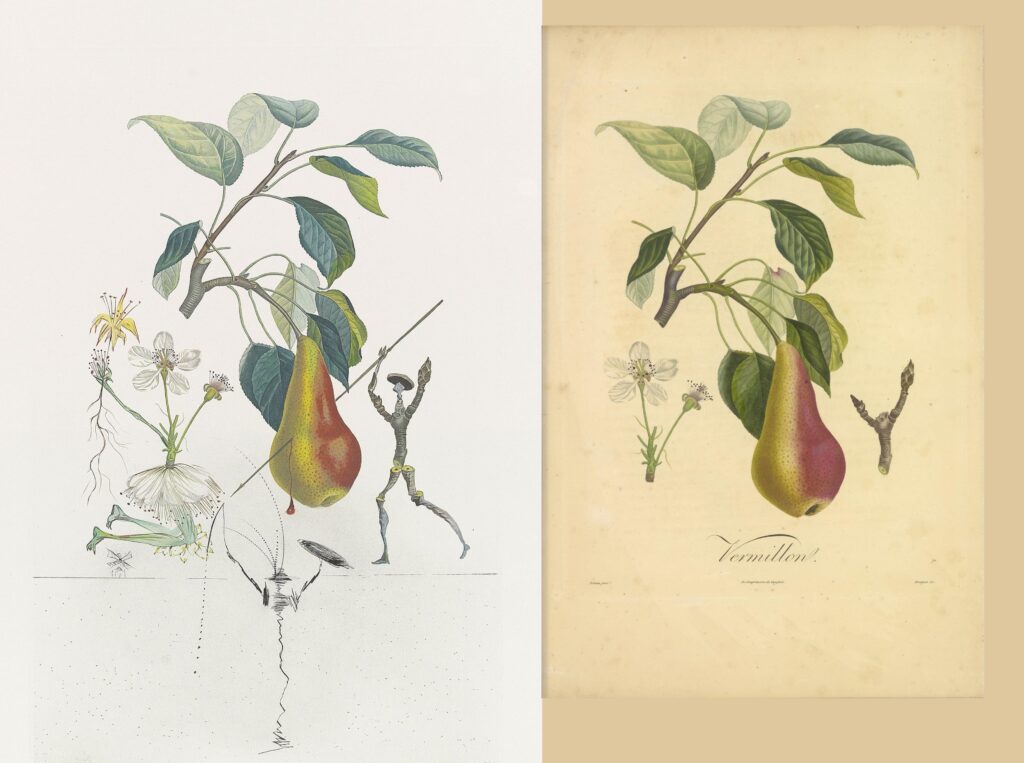

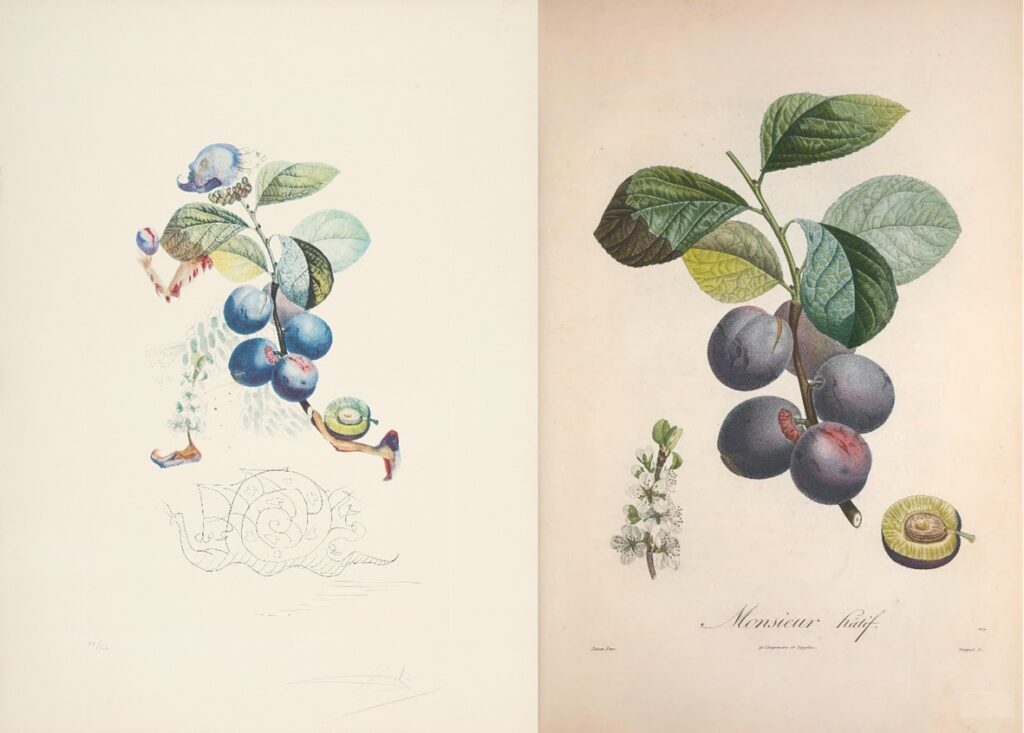

naturalist plates of Pierre-Antoine Poiteau and Pierre Jean François Turpin , two botanical artists of almost monastic rigor. Their work, imbued with scientific precision, meticulously captures every curve, every vein of fruits and flowers. And so Dalí, brushes in hand and imagination running wild, decided to make it his own playground. The result? A series of completely crazy lithographs called Flordalí , where the rigor of naturalist drawing collides with the flamboyant absurdity of surrealism.

When Dalí invites himself to the botanists

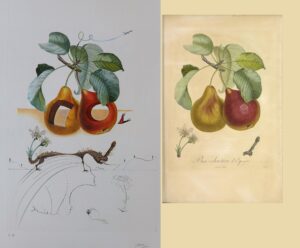

Imagine for a moment: Poiteau and Turpin spent years earnestly documenting nature, composing botanical plates worthy of the greatest scientific treatises. And then, Dalí arrived. He looked at a simple pair of pears and saw the scene of an epic battle. His Don Quixote , always on the lookout for new enemies, launched himself against… pears! Yes, pears! And that was just the beginning.

The cherries, under his brush, become a melancholic Harlequin, lost in an elusive reverie. An invisible tobacco smoke floats in the air, as if even nicotine had succumbed to Dalinian madness.

Further on, Poiteau’s carefully illustrated plums transform into a scene of courtly panic: a courtier flees at full speed, followed by a clearly threatening plum. It is unclear exactly what Dalí saw in these fruits, but one thing is certain: botany, in his work, takes on the appearance of a waking dream.

FlorDalí: when science becomes delirium

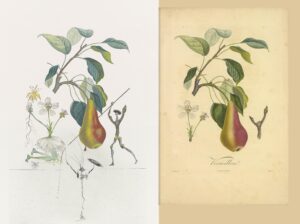

The FlorDalí series is a UFO in art history. Dalí didn’t just add a few surreal elements to existing illustrations; he reinvented them, dressing them with his whimsical humor and unbridled vision of the world. His compositions blend hyperrealistic botanical elements with dreamlike characters, chimerical creatures, and cryptic references to his own universe. Through FlorDalí, it’s a bit like a clown inviting himself to a scientific conference and starting to juggle with microscopes.

Take the blackberry, for example. In Poiteau’s work, it is detailed with extreme care, each grain meticulously shaded. In Dalí’s, it becomes a club chair in which a figure lounges, as if he had found the most comfortable sofa in the world. A perfect fusion of nature and the improbable.

Dalí loved to subvert codes and traditions. With Flordalí , he pushes irony to its paroxysm: taking works that embody scientific rigor and turning them into surreal visions full of mischief. He re-enchants nature by reinterpreting it in his own way, playing on the unexpected, the absurd, and the dreamlike.

Browse through the gallery below and compare Dali’s work with that of Poiteau and Turpin :

Why does Flor Dalí still fascinate today?

If this series remains so captivating, it’s because it achieves a feat: it brings together two seemingly incompatible worlds. On the one hand, botany, the domain of rigor and classification. On the other, surrealism, the realm of chaos and boundless imagination. FlorDalí is a bit like a scientist and a poet meeting for a game of cards where each trump card would be a new surprise.

Today, Flordalí lithographs are a steal on the art market . These works, true testaments to Dalí’s whimsical genius, fascinate art lovers and botany enthusiasts alike. They embody Dalí’s unique ability to see the world differently, to inject dreams into the most stark reality.

So, the next time you come across a 19th-century botanical illustration, beware… Perhaps, looking at it from a different angle, you’ll see a knight battling fruit, a Harlequin deep in introspection, or a blackberry sofa ready to welcome you for a surreal nap. Dalí understood this well: it’s all a question of perspective.

📖 Also read: Discover Poiteau’s other major works, such as Histoire Naturelle des Orangers, Traité des arbres fruitiers, nouvelle edition and Pomologie Française.